The Cocoa sector, historically acts as the spine of Ghana’s economy with an annual contribution of approximately $2 billion. Cocoa’s annual revenue contribution to Ghana’s economy is significant, with cocoa exports generating $2 billion annually, accounting about 25% of Ghana’s total merchandise export earnings and contributes to the country’s GDP. This helps in providing and sustaining about 800, 000 farm families. Cocoa production plays a crucial role in Ghana’s economy, making it a vital source of foreign exchange and employment.

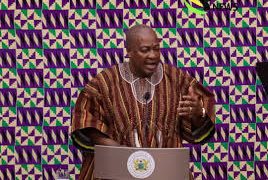

The sector is currently facing a structural heart attack. The emergency Cabinet meeting scheduled by President John Dramani Mahama for Wednesday, February 11, 2026, is more than a routine government briefing; it is a desperate attempt to resuscitate a multi-billion-dollar industry gasping for liquidity. For the Ghanaian farmer, the crisis is not found in balance sheets but in empty pockets and the silent warehouses of Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs). The current deadlock represents a failure of both old-school debt reliance and a premature leap into untested private-financing models.

The crisis has hit a breaking point as LBCs reveal they are owed approximately $185 million (GH¢2.04 billion) by COCOBOD. Samuel Adimado, President of the Licensed Cocoa Buyers Association, disclosed that some members have gone unpaid for two consecutive seasons. This massive debt has trapped LBCs between unpaid farmers and aggressive banks. While LBCs traditionally pre-financed purchases through bank loans, the nine-month reimbursement delays seen in the 2023/24 season have exhausted their credit lines. Consequently, LBCs now owe banks more than they owe farmers, effectively freezing the domestic buying market.

The current liquidity crisis, with over GH¢10 billion ($909 million) owed to LBCs, threatens the cedi’s stability. The central bank relies on the annual influx of “cocoa dollars” to shore up national reserves. While January 2026 inflation fell to 3.8%, the cost of agricultural inputs continues to rise. LICOBAG has called for a $200 million (GH¢2.2 billion) injection to purchase 300,000 tons of cocoa to stave off total collapse.

Beyond Borders: Regional Stability and Smuggling

The crisis is not contained. Last season, an estimated 160,000 tonnes of Ghanaian cocoa were smuggled into Côte d’Ivoire and Togo. This robs the state of revenue and undermines the Living Income Differential (LID) agreement. When one pillar of the cocoa belt cracks, the entire regional economic structure—and the farmers’ hope for a living wage, begins to crumble.

The proposed shift toward a “sustainable funding model” that avoids selling raw beans as collateral is ambitious. It aligns with the long-term goals of domestic value addition. However, you cannot build a factory on a foundation of debt and unpaid wages. The Wednesday Cabinet meeting must produce more than a communiqué. It requires a hard injection of cash and a transparent audit of COCOBOD’s operational costs to restore trust.

The Bottom Line: A Crisis of Trust

Ghana is no longer just competing with Côte d’Ivoire; it is competing with its own history of excellence. As the world watches, the Mahama administration faces a choice: a radical restructuring of COCOBOD or the slow-motion collapse of the nation’s most precious legacy. For the farmer waiting at the warehouse gate, policy papers are no substitute for payment. The future of the Ghanaian economy hangs on whether the state can once again prove that its cocoa—and its word—is worth the gold it is often compared to.